Academic freedom still lacking in several SADC countries

No country in the region reaches the threshold of being fully free for scholars to exchange and communicate research ideas and findings.

A study on academic freedom across the 16 member countries of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has concluded that no country in the region reaches the threshold of being fully free for scholars to exchange and communicate research ideas and findings.

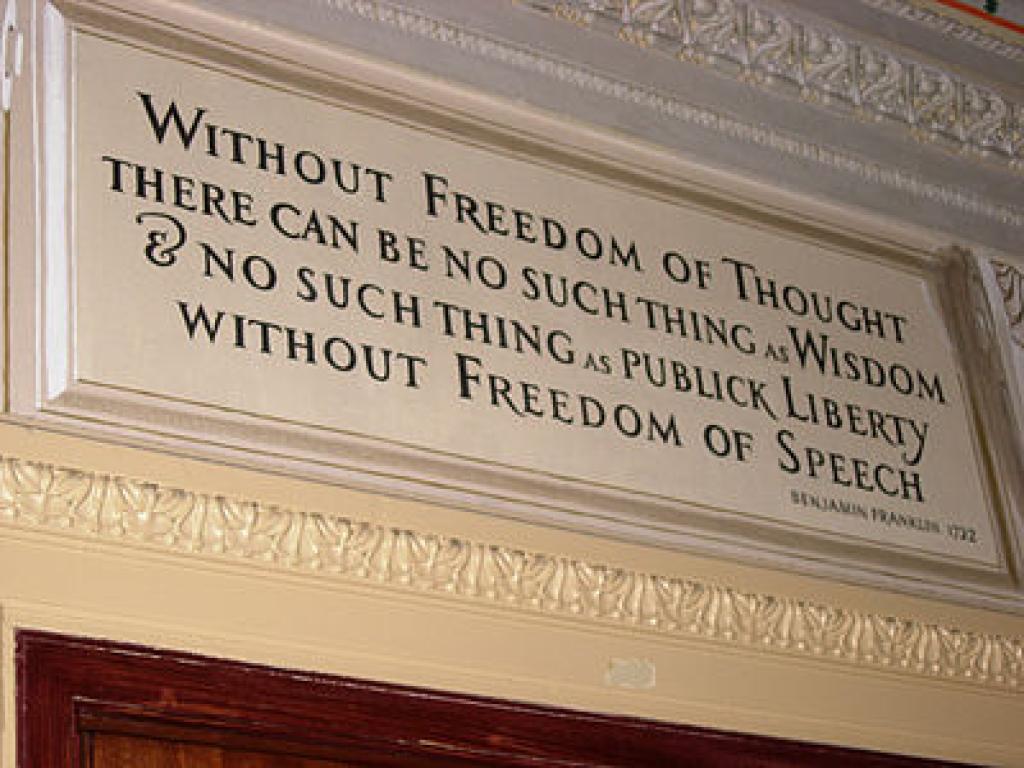

A report titled Freedom in SADC Countries (2013 to 2023), which was compiled by the Zimbabwe-based non-governmental organisation Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU), said academic freedom is conventionally considered a crucial component of democracy, alongside a free news media.

Universities and other higher education institutions, for instance, can challenge autocratic leaders, as students and academics are frequent critics of the state.

In its report, released recently, the organisation said the availability of large databases on democracy indicators allows comparisons of the democratic status of a country in ways that were previously very difficult.

It had used one such database provided by the Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem) to examine comparative performances in the development of democracy in countries across Southern Africa.

Indicators that included freedom of assembly and association as well as academic freedom, which RAU said showed the commitment in SADC towards an open society, leave much to be desired.

It looked at four indicators included in the V-Dem data: Freedom to research and teach; freedom to exchange and disseminate academic content; campus integrity; and the acceptance of academics as critics.

Freedom to teach and research

On freedom to research and teach, the report said it examined the extent to which scholars are free to develop and pursue their own research and teaching agendas.

Examples of interference include a non-academic actor censoring or restricting the drafting of research agendas or teaching curricula; external threats of possible reprisals against scholars leading to self-censorship; or the university administration abusing its position of power to impose research or teaching agendas on individual academics.

“The first of these, freedom to research and teach, is defined as the extent scholars are free to develop and pursue their own research and teaching agendas without interference.

“On the freedom to research and teach, with scores that can range from 0 (completely restricted) to 4 (completely free), the regional mean in 2013 was 2.73 and in 2023 it was 2.71.

“In general, it seems fair to conclude that academic freedom as the right to research and teach is supported in most SADC countries. Scores around 2, V-Dem argued, are indicating only moderate restrictions: when determining their research agenda or teaching curricula, scholars are occasionally subject to interference or incentivised to self-censor.

“However, several countries – Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zambia – move to the higher threshold (3), of being “mostly free” when determining their research agenda or teaching curricula.”

Academic exchange

However, the report said when it comes to freedom of academic exchanges and dissemination, the picture is more concerning.

The report said free academic exchange includes uncensored access to research material, unhindered participation in national or international academic conferences, and the uncensored publication of academic material.

It said free dissemination refers to the unrestricted possibility for scholars to share and explain research findings in their field of expertise to non-academic audiences through media engagement or public lectures.

Research, according to the report, is a broad term, and probably unproblematic for many academic disciplines, but some disciplines have the state as their focus, and research in the fields of economics, public administration, and politics can generate findings that are unpalatable for autocratic states.

It said findings critical of governments can also emanate from fields of study such as health and education, which can also generate findings that may irk governments. In this respect, the attitude of the South African government towards HIV/AIDS in the 1990s is a case example here. In this instance, former president Thabo Mbeki’s questioning of the link between HIV and AIDS affected health policies.

Thus, allowing research is one thing, but publishing findings can attract the criticism of governments.

“This indicator also refers to the unrestricted possibility for scholars to share and explain research findings in their field of expertise to non-academic audiences through media engagement or public lectures.

“Based on the scale of 0 (completely restricted) to 4 (fully free), there was a small decline from 2.78 in 2013 and 2.68 in 2023.

“Most countries range from moderately restricted, which means academic exchange and dissemination is occasionally subjected to censorship, self-censorship, to moderately free, in which case, academic exchange and dissemination is rarely subject to censorship, self-censorship or other restrictions.”

The ratings show a decline on this aspect in Botswana, Madagascar, Mauritius, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe, but improvements in eSwatini (slight), Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Seychelles, and Zambia.

“However, no country reaches the threshold of being fully free to share research,” the report cautioned.

The report said the sharing of research (as opposed to conducting research) is freer in Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, Seychelles and Zambia, but the freedom to do research without restrictions is better facilitated in Angola, Madagascar, Mauritius, Namibia, and Tanzania.

Campus integrity

The report said the indicator on campus integrity examines the extent to which campuses are free from politically motivated surveillance or security infringements.

It means the preservation of an open learning and research environment marked by an absence of an externally induced climate of insecurity or intimidation. Examples of infringements of campus integrity are politically motivated on-campus or digital surveillance and-or the presence of intelligence or security forces, student militias, or violent attacks by third parties, especially the targeting of universities to repress academic life on campus.

“Most countries lie in the range from moderately restricted to mostly free with only minor cases of surveillance or intimidation – but none being fully free. Six countries – Botswana, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia and South Africa – are performing worse on this indicator, but there are improvements in DRC [the Democratic Republic of the Congo], eSwatini, Seychelles, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe,” the report said.

Allowing critics

The last indicator measures the extent to which academic critics, including scholars and students, can actually criticise government policies.

The report said universities have a long history of being places of criticism of governments, even centres of resistance against autocratic governments, which are often viewed by governments as dissident behaviour.

It said public criticism of government policies can be conveyed through, for example, the publication of op-eds or social media posts on current affairs, the signing of open letters or petitions, the taking part in, or organisation of public protests, or the holding of critical lectures to students.

According to the report, most countries fall in the range where moderate to substantial criticism against governments and their policies are allowed, but only South Africa approaches the threshold of having complete freedom for academics and students to be critical of the government. “The freedom to criticise has been declining in 10 of the SADC countries,” the report said.

Impact of restrictions

In an interview with University World News, Dr Takavafira Zhou, who lost his job at the Great Zimbabwe University because he was seen to be a government critic, said he was branded an “academic terrorist” by authorities, with many universities subsequently shunning him – even though he won his case in court in 2012. He opted, thereafter, for consultancy work.

Zhou said he was once summoned by a vice-chancellor and told that he had insulted him and the then president of the country, Robert Mugabe, in his lectures. He was also allegedly told that a research paper he had presented in a seminar at the institution on the assassination of a leading liberation war fighter Herbert Chitepo was not welcome.

“I had delivered a lecture on the origin and development of civil war in Zimbabwe in the 1980s and the political development in Zimbabwe up to 2008 and that the problem could have been resolved without degenerating into a war.

“I actually stated that ‘You don’t need an AK-47 in order to kill a mosquito.’ That was interpreted as claiming heavy-handedness from President Mugabe and an insult to the vice-chancellor that could not be tolerated in a young university,” Zhou said.